Tanzania's New Inbound Remittance Fee: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.

A major shift is happening in Tanzania's remittance landscape. If you're in the payment industry—especially in the remittance and cross-border payment space—you’ll want to pay close attention.

This July, the Bank of Tanzania (BOT) issued a circular that fundamentally changes the rules for inbound remittances processed through the Tanzania Instant Payment System (TIPS). Effective August 1, 2025, every inbound remittance transaction sent via TIPS will carry an interchange fee of 1,000.00 TZS, payable by the sending participant to the receiving participant.

This is a big deal. On the surface, it’s about standardising a process, but its ripple effects could reshape the entire market. So, let’s break down what this new directive really means—the good, the bad, and the truly ugly parts of this new reality.

The Backstory: How Did We Get Here?

To understand the present, we have to look back. On March 22, 2024, BOT issued a directive instructing all TIPS participants to "immediately stop using TIPS for the disbursement of inbound international remittances". The official reasons cited were clear and valid:

Wrong Use-Case: The circular noted that inbound remittances are "international money transfers (IMTs), a different use case that is expected to be implemented in the Third Phase of TIPS development". They were being improperly processed as regular domestic transactions.

Compliance Violations: BOT specified that the practice "violates guidelines for Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism and Proliferation Financing (AML/CFT/PF) requirements". The circular detailed that these guidelines, among other things, "require sharing of transaction information, in particular, the originator and beneficiary information to enable real-time screening by all parties involved"—a process that wasn't happening correctly on the system.

This directive came when Tanzania was on the FATF "greylist" and the government was under immense pressure to tighten financial controls.

However, that's only one side of the story.

Some players in the industry argue it wasn’t really about compliance at all. They point out that mobile money operators were losing IMT business to banks, who could use TIPS to serve International Money Transfer Operators (IMTOs) far more efficiently. This advantage sparked some, let's say, lobbying. The thinking is that this was a calculated move by mobile money operators not only to slow the banks down but also to secure a share of the remittance revenue that banks were earning.

The evidence for this?

Selective waivers: Just days after the ban, BOT granted waivers to a few select banks upon request, allowing them to continue using TIPS for inbound remittances. This led many to ask: if “compliance” was the only issue, why grant exemptions?

Commercial disputes continued: The plot thickened even further. Despite BOT giving some banks the green light with waivers, some mobile money operators —and yes, they're being labelled as bullies—took a hardline stance. They blocked transactions from some of the approved banks, pointing to the absence of bilateral commercial agreements. This move made it clear the conflict was driven by competition and lost revenue, not just regulatory concerns.

So yeah, there was a lot of behind-the-scenes drama.

Why Were Remittances on TIPS in the First Place?

To understand this, let's look at how things worked before TIPS.

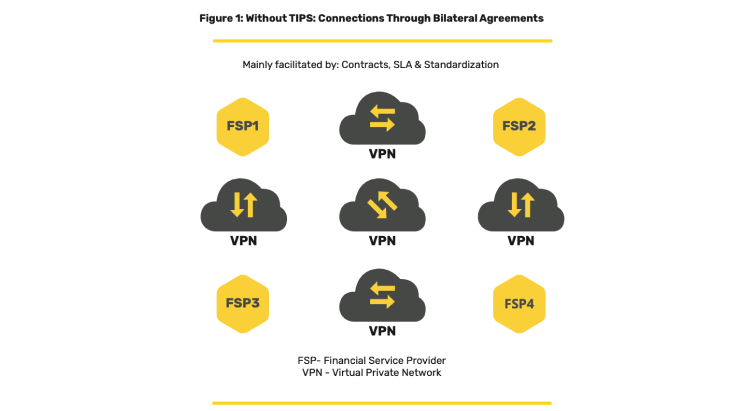

How things used to be: The Era of Bilateral Agreements

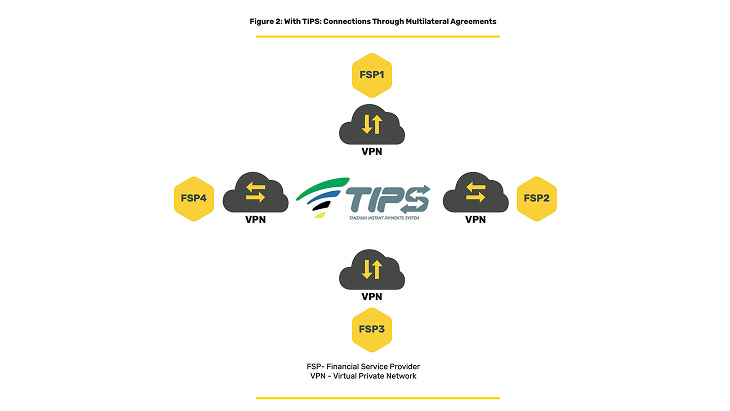

Before TIPS, interoperability between Financial Institutions (FIs)—like banks and mobile money operators—was handled through a web of bilateral agreements. Each FI had to negotiate and set up one-to-one technical and commercial connections with every other institution they wanted to transact with.

Just imagine the scale of that challenge in a market with over 30 commercial banks and 6 mobile money operators. A single bank had to maintain dozens of separate agreements just to ensure its customers could send money everywhere.

This created a complex, fragmented, and costly network. The system suffered from high transaction costs and limited interoperability, which were key constraints on the growth of digital finance.

The Solution: A Mandate for TIPS

The Bank of Tanzania introduced TIPS to fix these problems. One of the main goals was to replace the inefficient bilateral arrangements with a single, unified national switch.

To ensure its success, BOT took a decisive step: it mandated that all off-net transactions by different FIs must be processed through TIPS. This was done specifically to "dismantle the exclusive and closed-loop systems that bilateral agreements had created”

This mandate is the key to understanding what happened next.

Because all FIs were now required to use TIPS for domestic interoperability, they moved their operations to the new platform and naturally began to neglect their old, expensive bilateral connections.

What may have been overlooked was that some of these FIs (banks and mobile money providers) already had established partnerships with IMTOs for processing inbound remittances. With the mandate in place to use TIPS for all off-net transactions, it was logical and efficient for them to channel these international payments through the new, unified TIPS rails.

This is how TIPS became the de facto system for inbound remittance payouts, setting the stage for the recent regulatory changes.

The Good 👍

Let's start with the positives, because the new circular brings some clear benefits.

Clarity and Legitimacy: Inbound remittance is now an officially recognised use case on TIPS. No more grey areas or sneaky transaction blocking. This allows for proper transaction screening and more accurate reporting of remittance flows into the country.

Fairer Pricing Mechanics: The fee is standardised and set in Tanzanian Shillings, not US Dollars or other foreign currencies. This is a huge win, protecting IMTOs from the unpredictable and often premium exchange rates previously used by some partners. For once, pricing is local and transparent.

A Level Playing Field: This circular ends the monopoly held by the few participants who had waivers and opens the market to all TIPS participants on equal footing. IMTOs can now confidently use a single provider to disburse funds across Tanzania's entire financial network (bank accounts and mobile money accounts).

A Foundation for the Future: Establishing remittance as a formal use case creates a framework for future improvements, including the potential for outbound remittances through TIPS and other use cases. BOT has also stated the fee is "subject to review", which offers hope for future adjustments.

The Bad 👎

Now for the challenges, because this new fee introduces significant problems.

Remittance Just Got More Expensive: The TZS 1,000 fee will inevitably be passed on to the end-user. Because the circular doesn't specify how the fee should be collected, it will either be added to the sender's cost or deducted from the receiver's amount. Either way, sending money to Tanzania becomes more expensive for the diaspora.

To understand how this works, it's important to remember that the banks and mobile money operators in Tanzania are generally not the ones acquiring customers in the diaspora (They’re not the IMTOs) —that’s the job of IMTOs like NALA, Wise, Sendwave and many others. These IMTOs then partner with local FIs to disburse funds to the recipients who use these banks and mobile money services.

Let's walk through an example:An IMTO we'll call "IDK" needs to send money to a customer who uses a mobile money provider, which we'll call "Telco Red".

IDK partners with a local bank, let's call it "Bank Green," to process this payment through TIPS.

When Bank Green (the sending participant) sends the payment, it must pay Telco Red (the receiving participant) the TZS 1,000 interchange fee. But Bank Green also needs to make money, so it adds its own commission, let's say TZS 500.

This means the total cost for IDK to process this single transaction through Bank Green is now TZS 1,500 (TZS 1,000 for Telco Red + TZS 500 for Bank Green).

This TZS 1,500 cost doesn't just disappear. There are two likely scenarios:The Sender Pays More: IDK will likely pass the full TZS 1,500 cost on to the sender, either as a higher fixed fee or through a higher FX markup. The sender ends up paying more.

The Receiver Gets Less: Alternatively, Bank Green might choose not to charge IDK the TZS 1,000 interchange fee upfront. Instead, when IDK instructs them to send, say, 100,000.00 TZS, Bank Green will deduct 1,000.00 TZS from the payout, sending only TZS 99,000 to the recipient. The receiver ends up with less money.

Squeezing Already Thin Margins: For IMTOs that choose to absorb these costs to remain competitive, their profitability takes a direct hit. A TZS 1,000 fee on top of partner commissions, like I explained above, significantly reduces already thin margins. Of course, I can already see some IMTOs choosing to subsidise this, especially those chasing growth at all costs or those without local licenses that restrict them from sourcing FX from the black market, which helps them offset their costs. But for those who are running clean shops and doing things by the book? They're already finished.

Banks Could Lose Big: As we all know, formal financial services in Tanzania are dominated by mobile money providers —72% of Tanzanian adults use mobile money services, compared to just 22% for banks as of 2023. Obviously, the majority of remittance traffic terminates in mobile money accounts.

Now, IMTOs (not all of them, but certainly the big ones or those who are cost-sensitive) will be heavily incentivised to integrate directly with mobile money operators. Why? So they only have to pay the TZS 1,000 interchange fee instead of the fee plus a bank's commission.

Let's use our hypothetical example. Instead of paying "Bank Green" TZS 1,500, "IDK" could integrate directly with "Telco Red." By doing this, they would only pay the TZS 1,000 fee when sending to Telco Red's customers. Not paying Bank Green's TZS 500 commission means a 33% reduction in payout costs. In this climate, who would say no to that?

Banks might try to fight this, but I’m yet to see how they can win. Anything significant they charge above the TZS 1,000 fee just adds to the IMTOs' costs. I feel for the banks, but it’s a competition.A Step Backwards? This move pushes FinTechs, IMTOs, and payment hubs to reconsider the old, inefficient model of bilateral agreements. With these new costs added on top of TIPS, going back to direct deals suddenly looks very appealing for a few key reasons:

A direct integration with a bank for payouts to its own customers is often free or much more affordable than the new TIPS structure.

Some IMTOs already have better commercial terms negotiated with mobile money operators through their existing bilateral agreements.

Even if an IMTO decides to build integrations with each provider via TIPS, it can still be cheaper than using a single aggregator that will add its margin on top of the interchange fee.

This completely undermines the very purpose of TIPS, which was created to eliminate this costly fragmentation. Unless BOT mandates that all inbound remittances must go through TIPS (which is unlikely) and mandating it would create its problems, introducing a single point of failure for the entire country's inbound remittances, among many other risks.

The Ugly 🤢

Beyond the pros and cons, there are some deeper, more troubling aspects to this new circular (policy).

The Pricing is Discriminatory: After conversations with several IMTOs, a clear pattern emerged, summed up by one repeated question: "What's in it for us?" There’s no good answer, because this pricing model is structured to benefit the existing TIPS participants (banks and mobile money operators) who get to collect the revenue. It completely excludes the IMTOs, who aren't on TIPS and must use local partners to process their inbound traffic. In effect, IMTOs are locked out of a revenue stream they are single-handedly responsible for creating.

Penalising, Not Rewarding, Formalisation: IMTOs like NALA, Sendwave, Wise and many other play a critical role in bringing remittances and much-needed hard currencies into Tanzania's formal financial system. Yet, this policy offers no reward for that. Instead, it imposes a cost. It's like telling them, "We don't care how much it costs you to acquire and retain customers in the diaspora; after you've done all that, you must also pay an extra fee just to deliver their money."

Now, one might argue that local mobile money operators and banks also need to be compensated for their investment in acquiring the customers who receive these funds. That's a valid point. But the issue isn't that IMTOs refuse to compensate local partners—many have paid these FIs high fees for years. The real concern is whether the fee is fair, and that's where the conversation gets difficult.

Even if we set aside the direct transaction costs, the policy seems to ignore the massive, indirect revenue that banks and mobile money providers already generate from these payments. Banks and mobile money operators often make more money after the funds hit their ecosystem than they would from a simple incoming remittance fee.

And before someone whispers, "but mobile money operators let you take all the FX revenue," let's be clear: there isn't much revenue to be made in FX markups if you're running things by the book, especially when the government tightens control over exchange rates. The mobile money operators and banks know this themselves; they often lose out on bulk volume trades because their own rates are uncompetitive. Margins are small, and you can't always win on FX.The Risk of a Return to Cash: The Tanzanian market is extremely cost-sensitive. This new fee structure could make digital remittances more expensive than cash pickups. We may see banks and other players start promoting cash-based services again, running counter to the national goal of financial digitisation. Imagine NMB utilising its agent network for cash pickups, or CRDB, NBC, and Selcom MFB doing the same. You might think they don't have a large enough presence, but with the right incentives, they could scale cash pickup services rapidly. We've seen this happen in countries like Morocco, Ethiopia, and Egypt—Tanzania might not be so different.

Final Thoughts

BOT's decision brings welcome structure and clarity to inbound remittances. However, it does so at a cost that may stifle innovation, reduce competition, and ultimately hurt the Tanzanian consumer.

While a standardised system is a positive step, the question remains: Is this a foundation for a more inclusive ecosystem, or just a new tollbooth on the road to financial inclusion? We will be watching closely to see how the market adapts and whether the promise to review this fee materialises.

Lastly, let's give BOT its flowers. While we can critique the policy's impact, you can't imagine the amount of effort it has taken—on both the policy and the complex technical work required to get the IMT use case running on TIPS—to get this initiative over the line. For that, they deserve credit.

Sources cited:

BOT Circulars:

Ref. No. LB.422/535/03/36 TO: ALL BANKS AND ELECTRONIC MONEY ISSUERS RE: RESTRICTION ON DISBURSEMENT OF INBOUND MONEY REMMITANCES TRAFFIC THROUGH TIPS

Ref. No. LA.53/449/01/1263 To: TIPS Participants CIRCULAR ON DISBURSEMENT OF INCOMING INTERNATIONAL MONEY TRANSFERS/REMITTANCES THROUGH TIPS

Case study by BOT & FSDT: Building an Inclusive Payments Ecosystem in Tanzania through TIPS

FSDT FinScope Tanzania 2023 Full Report

BOT 2024 Annual Report - National Payment Systems

BOT 2023 Annual Report - National Payment Systems

BOT 2022 Annual Report - National Payment Systems

www.fiu.go.tz, accessed on July 23, 2025, https://www.fiu.go.tz/news/tanzania-has-been-removed-from-the-fatf-grey-list